Here to there: Study tracks wildlife movements locally

Published 4:12 am Tuesday, August 5, 2025

- Wildlife connectivity and mitigation are all part of new research project that impacts the area.

PSU research details animal movement in the local area – and how it can help

What are the trails, paths and directions that wildlife in the local area travel – and how can knowing that help?

Answering those questions was the thrust behind a recently released study that explored the travel behaviors of wildlife in and around the Canby and Molalla areas.

The study is part of a huge collaborative effort across Oregon, led by the Department of Fish & Wildlife, that has created an interactive map showing the areas of the state that are key “wildlife travel corridors,” where wild species move through to access key resources.

Trending

And yes, there are definitely wildlife corridors around Molalla and Canby.

The map can be used by many agencies; for example ODOT uses it to decide where they need to put wildlife crossings so animals can safely get across highways.

The Oregon Connectivity Assessment and Mapping Project datasets include movement corridors in and near the Molalla River corridor.

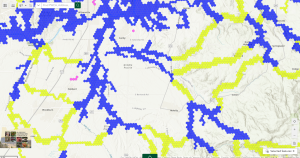

The regional area of a study group is in blue, while the ‘connector’ or travel routes of large animals is in yellow.

Key portions of Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas (PWCAs) can be found within natural riparian networks and forested areas between Molalla and Canby, influencing habitat linkages in the watershed region.

As both Molalla and Canby pursue Urban Growth Boundary expansions, OCAMP data can be incorporated into those zoning discussions to help preserve high-value connectivity zones outside urbanizing regions.

OCAMP supports ODOT and local transportation agencies in identifying road segments with high wildlife collision risk that intersect connectivity areas, a basis for installing wildlife mitigations like underpasses or fencing along key routes like highways 211 and 213.

Trending

Local infrastructure planners (e.g. SCTD transit, county road projects) can integrate connectivity data into design and mitigation strategies. Planning bodies (city councils, county commissions, etc.) are encouraged to overlay the PWCA map on future development proposals for informed decisions.

Watershed and habitat conservation efforts – Like Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) grants in the Molalla River watershed – can be prioritized using OCAMP insights, especially along stream buffer, shade, and riparian restoration zones that also overlap with PWCAs.

Local agencies (like Clackamas County, City of Molalla, City of Canby Bicycle & Pedestrian Advisory Committee, etc.) can use OCAMP maps to strengthen support for habitat-friendly infrastructure or conservation planning.

In the past, connectivity mapping in Oregon relied heavily on expert opinion, which left decision-makers without the robust data needed to guide policy and planning.

The OCAMP project filled a major knowledge gap, with science-based connectivity models for 54 species representing different movement patterns and habitat needs.

These models were combined to create the Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas Map, which offers a statewide picture of the most critical areas for wildlife movement.

“We used tracking data where we had it, and presence and absence data to validate where the animals were. Then we put all the species together. In the final map, what you notice about it is that it’s not for a particular species,” said Martin Lafrenz, a member of PSU’s geography department and the man who led the PSU research team. “It’s just animal corridors, generalized. If we are really interested in a specific animal, we can always drill back in the data. But what the Legislature wanted was just a map of animal corridors in general that they could use to say, ‘Okay, you’re going to do this project. It’s going to impact this corridor. So you need to put some kind of a crossing structure or fencing or some sort of mitigation.’”

How Can You Help?

The ODFW developed a project specifically for roadkill in Oregon which makes use of data from iNaturalist, an online social network for recording observations of wildlife.

“One of the things that we get asked a lot in our public communication is, how can the average person help provide information for connectivity?

And one of the best ways that we found to do that is with iNaturalist,” said Rachel Wheat, wildlife connectivity coordinator for ODFW and the overall project coordinator.

The state has some information on where large-bodied wildlife, like deer and elk, are killed on roadways, because their maintenance crews remove them.

But ODFW has very little information on smaller-bodied species. That’s where iNaturalist comes in.

“Anyone with a cell phone can go out and snap a photo of a roadkill observation that they see. And then we can draw on that information to help identify roadkill hotspots and find the areas where we really need to focus on doing some sort of mitigation, whether that’s crossing structures, habitat modification, or fencing to try to keep wildlife from getting killed on the road,” Wheat said.

With a wide variety of applications for individuals, organizations, and governments, the Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas map provides a critical tool for planning a connected future.

And for PSU researchers, OCAMP is an example of how science can inform policy and deliver real-world benefits.